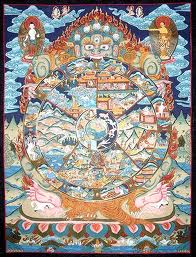

Although whatever is understood by transmigration or reincarnation does not strictly belong in this discussion on the “problem”, or the “reality” of death, it is so entrenched in people’s minds due to cultural and religious accretions, that a short account of it is not altogether out of place here. In the milieu of Hindu and Buddhist traditions reincarnation occupies the main doctrinal position in their exoteric or “religious” aspects, apart from belief in and worship of a deity or deities, and second only to the doctrine of karma – to which it is intimately related. Death of the body – the ‘gross body’ – is a foregone conclusion once it is irreversible (biological death).

A conventional account of reincarnation is as follows: ‘as for the jiva-atman carrying these vrittis, if during his lifetime the individual had performed some special acts of merit (punya) or demerit (papa), then the jiva-atman would proceed to heaven or hell. After spending his special karma-phala there, he comes back to the earth’. A more elaborate description is that once the seeker realizes nirguna Brahman he/she merges with Him/It, thus attaining immediate liberation (sadya mukti)’.Those who are eager to go beyond paths [the journey of life here and hereafter] tread no path’ (com. on Mu U. lll.2.6). ‘Just as the footmarks of birds cannot be traced in the sky or of fish in water, so is the departure of the illumined’ (Mahabharata). These two quotations are taken from ‘Methods of Knowledge’ – According to Advaita Vedanta’, by Swami Satprakashananda, p. 299.

Whatever path one has followed, the result of liberation is the same for all: ‘the cessation of all miseries and the attainment of the absolute bliss of Brahman’ (Vedanta-paribhasha Vlll, Conclusion – same source).

The fullest account of this doctrine, as I understand, can be found in Chandogya Up. V, 3-10, where Svetaketu, the incompletely instructed pupil, complains to his father that he was unable to answer the questions put to him by a kshatriya (which has given rise to the hypothesis that “there was a lively ambience of philosophy among the barons from which the brahmins were excluded” – The Essential Vedanta, ed. by Eliot Deutsch & Rohit Dalvi, p. 16 (2004). This is not the place to recount that story.

There are other realms or (eschatological) degrees or states of being, like the diverse hells, the purgatory and limbo of Christian theology and other, peripheral or central states (following René Guénon), through which the unsanctified soul passes. “No being of any kind can pass through the same state twice”; ‘peripheral’, and ‘central’ refer to animals and plants, and analogous to the human state respectively. All of this – except what is mentioned above about the ‘pathless path’ quoting Mu Up. and the Mahabharata – is popular or exoteric (and also cosmological) doctrine, interesting and stimulating though it be. A much deeper understanding of the doctrine of ‘transmigration’ is as follows:

The Greek philosopher Plato wrote: “The soul of man is immortal, and at one time comes to an end, which is called dying away, and at another is born again, but never perishes… and having been born many times has acquired the knowledge of all and everything”. It must be understood that Plato did not mean the individual soul as the subject of transmigration. Similarly, Plotinus : “There is really nothing strange in that reduction (of all selves) to One; though it may be asked, How can there be only One, the same in many, entering into all, but never itself divided up”. And Hermes, an important figure in Western esoteric doctrines: “He who does all these things is One”, and speaks of him as “bodyless and having many bodies, or rather present in all bodies”.

The distinguished and erudite former curator of the South-Asian Collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Ananda K.Coomaraswamy, begins his essay, ‘On the One and Only Transmigrant’, with these words: ‘Shankaracharya’s dictum, “Verily, there is no other transmigrant but the Lord” (BrSBh 1.1.5). Coomaraswamy referred in this context to the precedence in time of what is quoted above. He gave two foot-notes, the first for Plato, and the second for Plotinus:

(Meno, 81 BC… of the same sort is Agni’s omniscience as Jatavedas, “Knower of Births”, and the Buddha’s, whose abiñña extends to all “former abodes”. He who is “where every where and every when is focused” (Dante) cannot but have knowledge of everything).

(Plotinus, l4.9.4 5… In our Self, the spiritual Self of all beings, all these selves and their doings are one simple act of being; hence it is not the separated selves and acts , but rather the Real Agent that one should seek to know (BU 1.4.7, Kaus. Up. lll.8, Hermes, Lib. Xl.2. 12A). “Thou hast seen the kettles of thought a-boiling; consider also the fire!” (Mathnawi v.2902).

“Coomaraswamy is notorious for the profusion of his foot-notes and the multiplicity of his sources and the languages he uses.”

“Man is born once; I have been born many times” – Rumi. (AC’s quotation at the beginning of that essay).

Regretfully, though I have with me the original article mentioned here, I do not remember where I got this extended quotation of Coomaraswamy from, many of whose words and expressions are being reproduced here.