According to the teaching of Advaita Vedanta even the most well balanced people have an identity crisis (even if they don’t know it). If we meet a person who claimed to be Napoleon we’d most likely quietly cross to the other side of the room. The ancient sages of India, despite knowing that most of insist we are characters very different from who we are in truth, are slightly more accommodative of our self-delusion and try to help us rise above it. Everyone is born ignorant of the world and also of the truth of one’s identity: that is part and parcel of the human condition. Worldly ignorance is relatively easy to overcome, but self-ignorance requires subtle work and takes longer.

It is a rare person, says the Upanishad, who turns back from worldly involvements and wants to know who the observer is. Most, however, remain firmly fixated in their partial views of who they are, and end their lives deluded. The view is partial because they know ‘I am’, but do not know what ‘I’ is: and never even think that it is worth the enquiry. It’s not just the Eastern tradition that finds this a waste of a human embodiment, the same sentiment is also evident in the Western tradition in the words of Socrates: ‘An unexamined life is not worth living.’

To be a seeker of the truth of one’s identity is a high achievement; to be a committed seeker is even higher. In acknowledgement of the quality of the serious seeker, traditional teachers of Vedanta set the bar high. The level of precision they expect is exacting: words are precise tools in the hands of a master teacher. Before talking about the nature of self-delusion and its antidote, therefore, it is as well to establish the meaning of the verb ‘to identify’ because we are all identified with characters we are not (ever the character of ‘truth seeker’) and the shedding of our false self-identity is part of the solution.

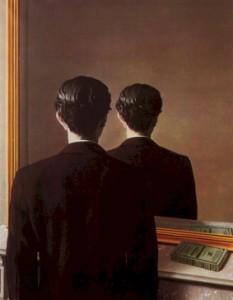

The verb ‘to identify’ has two aspects: to recognise (we identify a person from the police line up); and to associate with (we identify with being German or Indian or Christian or Hindu etc). To acknowledge these two meanings is important as they are two sides of the same coin and are both involved in our self-delusion.

We identify people and things by being very familiar with their distinguishing features: the more precise and detailed and unique the features, the more certain our identification. It may be good enough to say, for example, that the person is a man; better to say a tall man; better still adding: ‘with long blonde hair and a moustache’. Even this, however, could serve as a description of many men. But then as we add scars, tattoos, colour of eyes, etc we eliminate more and more people from the line-up till there is only one that fits the description.

‘To associate’, the second meaning of the word, ‘to identify’, follows on from absence of the first, ‘to recognise’. If I don’t recognise something for what it is, I take it to be something that it is not and then superimpose on it, by association, all of the qualities of the thing I erroneously believe it to be. The famous example in Vedanta is, in a semi dark room, we mistake a rope beside the bed for a snake. First I don’t recognise the rope to be a rope in semi darkness. Then I mistakenly identify it as a snake and, assuming my false identification to be the reality, I react to the rope as though it really is a poisonous snake. The only basis for the ensuing distress is ignorance, and thus the only antidote to this situation is knowledge. Note, that it is not knowledge of snake that is the antidote, but it is knowledge of the rope. When I see the rope as a rope the snake is no more. Similarly we will get rid of our self-delusion for good by really knowing what Self is.

Of course in the snake-rope example we can examine the snake – if one is brave enough! It doesn’t move; it doesn’t seem to have a head; its tail is unusual – looks frayed! But, still, if we have no knowledge of a thing called rope, we aren’t really sure of what we’re looking at. And insecurity and tension may persist.

How does all of this apply to the seeker of the truth of the ‘I’?

The spotlight eventually falls on the ‘I’ when a person starts to enquire into life’s big questions: Who am I? What is this universe? How does it all come to be? With some grace we arrive at the question that starts us off on serious enquiry: Am I really what I take ‘I’ to be? To get a clue about what ‘I’ is commonly identified with, all one needs is to is become sensitised to habitual statements such as: ‘I am not beautiful’ (body), ‘I am ill’ (physiological functions) ‘I am sad’ (mind), ‘I don’t understand’ (intellect), ‘I am not that sort of person’ (ego).

Some may argue that these are necessary expressions for everyday communication. Here’s where traditional teachers demand a different sort of rigour: self-honesty. When I say I am sad, are these the words of a detached, unmoving, dispassionate observer who is merely observing the rise and fall of the emotion of sadness in the mind? Or is the ‘I’ emotionally entangled, overwhelmed by the feeling of sadness with all its accompanying effects: coldness in the belly, tears, constriction in the area of the heart, and the rest? And, even if wallowing in sadness is merely momentary, stemmed by the voice of reason that says that sadness is not the truth of the self (or other such words that are used to get one out of the rut of habitual emotion) the fact is that one had slipped – albeit momentarily – into identification with the emotions: ‘I’ became ‘sad’. (And, if one was to be really vigilant, one could ask if the act of stemming the sadness was accomplished by using words to talk oneself out of the feeling or by using memory of good advice or other such stratagems. And, if we did, were these words under detached observation or did ‘I’ become the ‘discriminator’, ‘the adviser’, the strategist’?)

If ‘I’ is in emotional turmoil or ‘I’ is the wise adviser or if ‘I’ is identified with any role whatsoever, then you can be sure that observation needs to be finer, that enquiry needs to continue, because ‘I’ is not really known. The moment the rope beside the bed is known to be a rope, we will never mistakes it as being a snake or anything else for that matter. Is it possible to assume, similarly, that once we recognise the Self for what it is, we will never mistake it for something else? Is it possible for one to hold knowledge without change? Being firmly established in knowledge is not something uncommon or mystical, we are well practiced in it: if someone calls you a dog you know that you are a human being. That knowledge is unshakable (unless there is some damage to the organ involved in knowing). We can safely assume, therefore, that the moment the truth of oneself is known, we are unlikely to become identified again with any minor character that strut its time upon the stage.

The inevitable consequence of identifying ‘I’ with either the body, or the life functions, or the sense powers, or the emotions, or the intellect or any job title or role, is insecurity. The body is never perfect, so I am imperfect. My knowledge is never complete, so I am incomplete. My emotions are inappropriate so I am guilty. And thus it continues: there is always someone better and that threatens my security and rubs up against my ego, causing unhappiness. That’s why we can say that even the most well-adjusted person (at least ‘well-adjusted’ in the eyes of society) will inevitably suffer from insecurity and unhappiness from identifying with the body, mind, etc – in other words, they too will have a crisis of identity.

Vedanta encourages one to ask: Am I really this limited character? Is unhappiness and insecurity inevitable? Are they intrinsic to my nature?

The ancient sages offer a series of analytical methodologies to assist with these lines of enquiry. And gradually, like the brave person who, on realising that no amount of shouting and banging and throwing stones at the rope-snake drives it away, tentatively approaches it to take a closer look, we embark on the journey of self-discovery. It may not be easy at first to determine who we are, but we are certainly able to determine what we are not. With each step we see that we are not this, not that. How do we go about it?

Initially, simple logic is our tool: if I can observe something then ‘I’ cannot be that thing. We start off quite rationally and look around us at the world and know that I am not things like tables and chairs and trees and sky. Why? Because I am here and they are there and I am the one who is observing them. So where does ‘here’ begin? It begins with my skin: even something very close to skin, such as hand cream, is not ‘I’.

But, how can I be the body when ‘I’ is the one who is observing the body: I can see hands and legs and skin and fat and blood and scars etc? Does skin think: I am skin? No. ‘I’ think: I have skin. So watch out the next time the skin is cut and you say: I am bleeding. (It may be a common expression, but see if, at the time, the ‘I’ is identified with that from which the blood is pouring.) Similarly we realise that ‘I’ am aware that I can hear, touch, see, taste or smell. I know whether or not I can walk or what strength I have in my arms. I know what I am feeling and thinking. That means that I cannot be the power behind the organs of perception or action, nor can I be the mind or the intellect. Who, then, is this ‘I’ and where is it based?

The answer of science is that ‘I’ is an amalgam of electro-chemical impulses (i.e. for science we are nothing but gross matter) and that ‘I’ is located in the brain. In that case, let all who desire to achieve mental equanimity (and accept this scientific view of consciousness) stop right here and now because a material, ever-changing, never-still ‘I’ can never find peace.

Vedanta presents a different view. It says that ‘I’ is other than the body, physiological functions, senses, mind, intellect. The analytical process it provided to start off this enquiry is the equivalent of approaching the snake that one imagined one saw in the semi dark. At some point we become convinced that what lies there is NOT a snake. Applying this to self-enquiry, we realise at some point: I am not all these physical, psychological, mental functions I take myself to be – functions that I am identified with. The fear should subside at this point and, to a certain extent, it does.

But here’s the rub…

Assuming that one was not familiar with something called ‘rope’ then, having eliminated the snake as being a false superimposition, we still do not know what is lying there by my bed – however close we get to it! Similarly, every night in deep sleep we get to a point at which the mind and memories and external word and sense powers and emotions, and even the ‘I’ thought itself, are not superimposed on who I really am. Mind is totally still. It’s a blank. In this state are we confronted with Self as pure existence, not attached to any object or function, but we do not recognise what is being seen. In deep sleep, we reach the position that is the goal of deep meditation, the total restraint of mind, but all that is known on waking is that ‘nothing’ was known at the time. Yet Self was inevitably present. It didn’t vanish. It’s there on waking.

On waking we say: I slept well. I knew nothing. So this thing called ‘I’ must have been there in order to report, on awakening, what it knew. So what we take as ‘nothing’ in deep sleep cannot be non-existent. The only problem is we cannot ‘identify’ it as ‘I’ because we are not yet familiar with what the Self is.

The teachings of Vedanta – the Upanishads and Bhagavad Gita – have, as their sole purpose, the task of correcting our ignorance about the Self. When that ignorance goes so does our own personal self-ignorance and, with it, our identity crisis. When the true nature of Self is dis-covered (i.e. had the false cover of identification removed from it, and it is indicated clearly and by spiritual teachers) then we can shout with joy: I am That Self!