The Kaṭhopaniṣad with Śaṅkarabhāṣyam

Based on Swami Paramārthānanda’s lecture

Compiled by Divyajñāna Sarojini Varadarājan

The main teaching of the Kaṭha Upaniṣad is Death’s response to the request by a young seeker, Naciketas, for Self-knowledge. Any serious student of advaita will want to know the answer as this is our own question too: using logic we may well be able to arrive at what we are not, but we still need to know clearly what we are. For this reason this book by Smt. Sarojini Varadarajan, based on Swami Paramarthananda’s traditional unfoldment of the Upaniṣad and Śaṅkara’s commentary theron, is a valuable addition to any seeker’s library.

The main teaching of the Kaṭha Upaniṣad is Death’s response to the request by a young seeker, Naciketas, for Self-knowledge. Any serious student of advaita will want to know the answer as this is our own question too: using logic we may well be able to arrive at what we are not, but we still need to know clearly what we are. For this reason this book by Smt. Sarojini Varadarajan, based on Swami Paramarthananda’s traditional unfoldment of the Upaniṣad and Śaṅkara’s commentary theron, is a valuable addition to any seeker’s library.

One way of approaching this Upaniṣad is to note that Naciketas standing at Death’s door (literally) remained steady-minded enough to press his request for Self-knowledge – in spite of Death’s initial resistance to answer. And, by the end of the Upaniṣad, after Death finally gave in to the young man’s request, Naciketas ‘became pure and immortal’. Is it really possible that we can also reach the same point by closely following the teaching that Naciketas hears, especially as we are living lives grounded in fear?

The pain of life that most people experience has its roots in fear: fear of inadequacy, fear of loneliness, fear of being unlovable. And the whole of life, as a consequence, is driven by our vain attempts to eliminate fear, to find peace and contentment through people and things and pleasurable activities, through building a reputation (for most people, secular; for some, religious or ethical), or through securing a place in heaven.

Underpinning all fears is a single fear: I am mortal, at any time I could die. So imagine the scenario in which Death, himself, feels so bad about not treating you with due respect that he grants you any three boons. This was the situation of Naciketas.

For his first boon Naciketas asks that his father may become free from anxiety and anger and find peace. For his second boon he asked for details of the rituals that would deliver heaven as its reward. Thus the first boon was for his family and the second for society. The third boon he asks is for his own benefit: Self-knowledge, ātmājñānam.

The Upaniṣad makes explicit a number of key preparatory aspects accepted by traditional advaita teaching, such as the qualification of the student – dispassion, mastery over mind and senses, etc – as well as total clarity that the desired end of mokṣa means self-knowledge: (Naciketas would not be diverted by any of the rich array of worldly pleasures that Death offered him to change his request for his third boon). It also emphasises the limitation of logic (the main tool of those who do not have access to the vedānta mantras) and of the role of śāstram in the hands of a qualified teacher as the only means of knowledge (pramāṇa) of Self (1.ii.7-9).

This Upaniṣad is rich in the wisdom that we find (sometimes almost verbatim) in other Upaniṣads as well as in the Gītā. It introduces key concepts such as śreyas and preyas, the spiritually good and the worldly pleasures, together with their merits and limitations (1.ii.1-2) – Arjuna’s request for śreyas in the Chapter 2 v7 of the Gītā is what releases Lord Kṛṣṇa’s teaching. Also in this Upaniṣad we find the familiar metaphor of the body being a chariot with Self as the charioteer (1.iii.3-9) as well as the popular mantra chanted at ārti times: Na tarta sūrya bhāti, na candra tārakam… (There the sun does not shine, neither do the moon and the stars…) (2.ii.15). It also gives us the image of the upside-down tree with its roots above and branches below referred to by Lord Kṛṣṇa in Chapter 15 of the Gītā (2.iii.1).

And anyone keen to know the answer to Naciketas’s question will be very satisfied with the comprehensiveness of Death’s description of Ātmā and some of the traditional methodologies employed in enquiry: the analysis of the five sheathes, the discrimination between seer-seen, the analysis of the three states of experience, etc.

This methodical and thorough piece of scholarship took the author around two years and 600 pages to complete. It is structured as was the author’s previous book on the Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad:

• An introductory overview of each verse in which key points are brought out to provide valuable insights into the heart of Śaṅkara. In the introduction to the 1.i.20, for example, we learn of the significance of the three boons according to Śaṅkara. The first two boons (for father’s peace and for the rituals that take one to heaven) ‘represent the entire dvaita prapañca’ (universe of duality), the subject matter of the karma kāṇḍa (ritual portion) of the Vedas. ‘Accepting duality or non–self temporarily is called adhyāropa, or superimposition. This is a very important first step in advaitic teaching. Later you come to apavādaḥ, which is falsifying or negating the superimposed dvaita anātmā.’ This second step is represented by the third boon requested by Naciketas. This sort of information only comes to the surface from study with a traditional teacher: it is valuable because ‘the teaching is complete only when you go through both adhyāropa and apavādaḥ.’ Traditional teaching is unique in recognising that without both steps one is likely to remain stuck in duality.

• Next we are given the mantra verse in Devanāgari script followed by a transliteration in roman script and the Sanskrit verse in prose order (with missing words added in to render poetry into prose).

• This is followed by a word-by-word translation, followed by a clear prose translation of the full verse.

• Finally we have the Sanskrit text of Śaṅkara’s commentary with a lucid translation of it. In some places where ‘technical’ words need further explanation, this is done by way of footnotes.

This, however, is not a book for total beginners. Some Western seekers might be put off by the amount of un-translated Sanskrit in the text (Death, for example, remains un-translated as Yamadharmarāja throughout). Also typographically, the different layers of the text could do with being distinguished a bit more clearly so that one knows what’s introduction, what’s translation, what’s commentary. But these are small niggles, as any student who is seriously interested in penetrating the wisdom of Death’s teaching will be very happy to have a copy of this book at hand. The understanding it makes possible holds out great rewards:

“Naciketas completely acquired this knowledge along with the method of yoga which were taught by Yamadharmarāja. Thus having attained Brahma he became pure and immortal. Anyone else also, by thus knowing the ātmā (can attain Brahman).” (2.iii.18)

Hardback, 28pp intro +596pp text

Price Rs.200 + postage

From

Selva Nilayam

No.13, Circuit House Road

Coimbatore 641 018

Email: sntpl@dataone.in

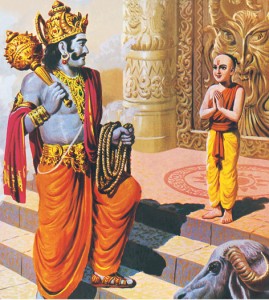

Image from cover of Amar Chitra Katha comic ‘Nachiketa’