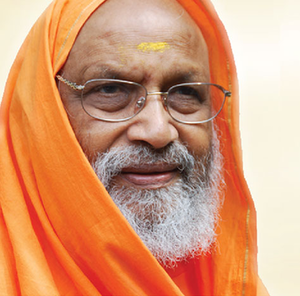

Homage to Pujya Swamiji

D.Venugopal

Pujya Swamiji’s uniqueness has already been the subject matter of a book by that name, published in October 2008 and released by Pujya Swamiji himself. However, certain very significant details of his life and teaching need to be highlighted.

I

Right from his childhood, Pujya Swamiji was distinctively different from others. He was fearless by nature. He did things that others never dared to do, like catching any snake by its tail. During those days, owing to the anti-Brahmin movement, the school boys used to rag the Brahmin boys, who were conspicuous with their tufts. Pujya Swamiji also had a tuft. He once caught off guard a tough ragger and punched him so hard that he fell into a ditch. Also, for fear of being ragged, the Brahmin boys would not opt for Sanskrit as the second language. Unmindful of the repercussions, Pujya Swamiji chose Sanskrit. He did not also take lying down the ridiculing of religious practices by his class mates but countered them by thinking out the plausible reasons for those practices. They could never outwit him in the arguments that ensued.

Pujya Swamiji had no sense of possession even initially. He always gave away what he had, if others needed it more. This was the dominant trait in him. For instance, even when his family was dependent on the income derived from the coconuts that grew in their field, he gladly gave some of them to the landless farmers. His widowed mother, for her part, never asked him not to give, even while reminding him that their family could not afford that level of generosity.

Even as a boy, he had absolute trust in the śāstra. At the time of his upanayanam, the village purohit told him of the value of Gāyatri japa and asked him to chant it 1008 times every day. Pujya Swamiji did so religiously until his sanyāsa.

Most significantly, his actions were in accordance with the knowledge he had on the subject. His father passed away when he was hardly eight. He was the eldest surviving son. All were crying. Pujya Swamiji was reminded of a Tamil verse to the effect that even if you mourned forever, the dead would not return. He did not cry and told himself that he had to face facts. He remained undisturbed and tried to persuade others to stop crying. When he did not succeed, he went out and joined the boys who were playing.

Even with the responsibility of the family on his young shoulders, he was never worried or depressed. He was joyous. He spontaneously did what was appropriate in a given situation. In sum, even in his childhood, Pujya Swamiji was, to use Swamiji’s expression, “a complete man”, grown to the level that it is possible to grow. No wonder that his attending of the yajña on Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad conducted by Pujya Gurudev Swami Chinmayananda at Madras turned out to be the decisive moment in his life. While what was taught sounded familiar to him, he could not make out the message of the Upaniṣad. But it made such a tremendous impact on him that finding it out became his only goal in life. To achieve it, he got detached from his earlier associations and activities. He also left his job when two of his younger brothers became employed. Then, he became the first sevak of his guru and totally involved himself in the pursuit.

As a sevak also, Pujya Swamiji was a class by himself. In a satsaṅg, Pujya Swamiji stated that no one could serve his guru as well as he did. His very first assignment bears this out. He was sent to Bangalore for bringing out the monthly “Tyagi”. The accommodation arranged for him turned out to be a small garage overlooking a gutter. Nothing else was provided for. Often, he had to go without food. Money was lacking not only to meet his daily needs but also to bring out the publication. Even so, he managed to accomplish the work that his guru had assigned him without ever troubling him. Nothing mattered to him when it came to serving his guru.

Towards the final days, when Pujya Swamiji decided to resume the treatment at the request of the Prime Minister, he said that he broke his saṅkalpa for the first time. It means that he has always being doing what he undertook to do. Indeed, he was totally unlike us in every respect even though he lived like one of us.

II

In regard to unfolding of the śāstra by Pujya Swamiji, very significant aspects would bear reiteration. Pujya Swamiji gave the entire vision of Vedānta all the time. The crux of Vedānta lies in the fact that even while Brahman is the cause of the manifestation, Brahman has no connection with it. There is no reciprocal relationship between Brahman and the manifestation since Brahman has substantiality of its own or is satyam, while the manifestation is mithyā as it has only borrowed substantiality from Brahman. If we want to count as to what is existing, the manifestation, which is without substantiality cannot be counted as an entity. It cannot also be totally left out since it is experienced and has transactional or empirical reality. So, in real terms, what is there is neither a single entity of Brahman (monism) nor two entities of Brahman and the manifestation (dualism) but non-dualism of satyam Brahman with mithyā manifestation or a-dvaita. In order to present a-dvaita all the time, when Pujya Swamiji has occasion to say, for example, that jīva (which is part of the manifestation) is Brahman, he would immediately add that Brahman is not jīva.

It is also entirely due to Pujya Swamiji that we properly understand Īśvara and are able to cognitively bring him into our lives and end our lifelong feeling of helplessness. We were totally helpless as a child but felt secure owing to the absolute trust we had in our mother, whom we considered as infallible. On discovery of her limitations as also of others, we had no alter of trust. As for Īśvara, we had the wrong concept that he is the Almighty who will fulfil all our prayers. When it was belied, we lost trust in him also. It was Pujya Swamiji who provided us with the knowledge of Īśvara, which would free us from helplessness. He clarified that as the material cause of the body-mind-sense complex and jagat, Īśvara pervades them as the material. As intelligent cause also, he is all pervasive, since the body-mind-sense complex and jagat are manifestation of his knowledge in the form of physical order, physiological order, psychological order, cognitive order, logical order and value structure in the form of dharma. Since Īśvara is all-knowing, the order is infallible. We, with our free-will, are within this infallible order. With the knowledge that nothing can go wrong in this order, we can relax, face the world objectively and end our sense of helplessness.

More importantly, Pujya Swamiji’s exposition of the order pervading the entire manifestation as Īśvara is to enable us to assimilate the knowledge that “I am the whole” and “I am Īsvara”. Assimilation of this knowledge is a problem for many of us. In a satsaṅgh, Pujya Swamiji explained the source of this problem and provided the solution. He said:

“The whole involves spheres. Generally, we gloss over many spheres. And there are corners in our buddhi also where there are reality conclusions, political conclusions, sociological conclusions and some value structure conclusions. Some prejudices are there. They are all opposed to the knowledge. These are all pratibandhas. All these have to go. The assimilation of my being everything implies all these dark corners being ventilated, light brought in. I find the conclusions are too many. And all in different spheres. That is why I brought in this assimilation process in the form of Īśvara’s order. It is very crucial, critical. What I did, I divided Īśvara as though into different orders. And then one Mahā-order so that I can cover the areas where I can be caught up. So Īśvara in every area: the physiological area, psychological area, biological area; so many areas where conclusions may be there.”

With the assimilation of the knowledge of the Mahā-order, all our conclusions give way to the awareness of Īśvara bringing us to the threshold of recognition of our true nature.

III

What can be our homage to Pujya Swamiji? Not just singing his praise but by our own transformation through the knowledge that he has imparted and spread that knowledge. That is the least and the best that we can do. Om.

D. Venugopal is the author of the books ‘Pujya Swamiji Dayananda Saraswati: his Uniqueness in the Vedanta Sampradaya’ and ‘Vedanta: the solution to our fundamental problem’. The latter is serialized at this site, beginning here.