This is the first of a 3-part blog that I originally posted to Advaita Academy, on the subject of the pa~ncha kosha prakriyA, probably better known to most as the metaphor of the ‘Five Sheaths’.

Simplistically, this is the idea that there are various levels of identification of ‘Who I really am’ with aspects of the body-mind and that these have to be recognized and dropped so that I can realize my true nature.

However, because of the way that this idea is sometimes presented, there is often a serious misunderstanding on the part of the seeker who, taking the metaphor in a more literal sense, mistakenly believes that the self is literally ‘covered over’ by these ‘layers’ and somehow has to be ‘uncovered’, like some Russian doll. This misunderstanding may be reinforced by the notion of the Self being ‘hidden in the cave of the heart’ – another potentially misleading idea that I have discussed before.

I myself was confused by this prakriyA back in the days when I wrote the first edition of ‘Book of One’. Here is what I said then:

It has been noted above that ‘I’, the real Self, ‘identifies’ with the body for example, with the end result that I think I am the body. There is a system in Vedantic literature that describes these various layers of identification. They are referred to as ‘sheaths’ (Sanskrit kosha) which cover over our true essence in the way that a scabbard covers a dagger or sword.

The rest of the description was fairly innocuous and largely correct, apart from the repetition of the concept of ‘covering’. I reproduce it below so that anyone unfamiliar with the metaphor can understand what we are talking about:

The first of these layers – the ‘grossest’ and the one with which we first tend to identify – is the body. This is referred to as the sheath made of food (annamayakosha). The body is born, grows old, dies and decays back into the food from which it originally came (well, food for worms anyway) but this has nothing to do with the real Self, which is much closer than hand or skin.

The second layer is called the ‘vital sheath’ or sheath made of breath

( prANamayakosha). Hindu mythology refers to the ‘air’ as breathing life into the body. We might call it the vital force by means of which the body is animated and actions are performed. Although this force derives from the Self, as indeed everything does, it is not the Self. We each of us tend to believe that we are somehow immortal. Although we acknowledge that the body must eventually die we feel that there is this animating force which will survive that death. This is the identification with the vital sheath.

(As an aside here it is worth noting that, from a vyAvahArika standpoint, the teaching is that on the death of a non-realized person a ‘minute body’ is assigned to the jIva so that the subtle body, prANa-s and sense organs etc can accompany the jIva in the process of preparation for the next rebirth. But let’s not allow this to confuse the issue!)

The next layer is the mental sheath consisting of the thinking mind and the organs of perception (manomayakosha). This is the part of the mental makeup responsible for transmitting information from the ‘outside world’ but which usually gets up to mischief that is really none of its business, i.e. thinking and trying to understand everything. The Sanskrit word for this ‘organ’ of mind is manas. This is probably the sheath with which most of us identify.

Beyond this, however, there is the higher faculty of mind, responsible for discrimination, recognizing truth or falsehood, real or unreal, without recourse to mundane things like thought and memory. In silence, it knows without needing to think. We might call this the intellect; Sanskrit calls it buddhi. It is responsible for such judgments as Solomon’s in respect of the two mothers claiming the same child. He suggested sawing the baby in two and giving half to each woman. Supposedly the false mother agreed to this while the real mother said that the other woman could have the child. This is the intellectual sheath, vij~nAnamayakosha.

Some readers who meditate may have been fortunate enough to experience moments of the most profound peace and silence, when the mind is completely absent and a feeling of deep contentment can be felt. It might be thought that this is the state of realization for which we are aiming, if only it could be maintained. Instead it lasts mere minutes or, very rarely hours for a few dedicated ascetics. But no, this is just another state, albeit perhaps a desirable and blissful one. We are still observing it and therefore cannot be it. It is the final sheath, called appropriately enough the ‘Bliss’ sheath (Anandamayakosha). Because of its supremely blissful nature, it is reputedly the most difficult of the sheaths to transcend.

What we truly are, then, is the ‘Real Self’ or simply ‘Self’ with a capital ‘S’ as it will be called in this book. But, through identification with these various layers or sheaths, this Self is obscured. It is like water contained in a colored glass bottle. The water itself seems to take on the color of the glass, though it is itself colorless.

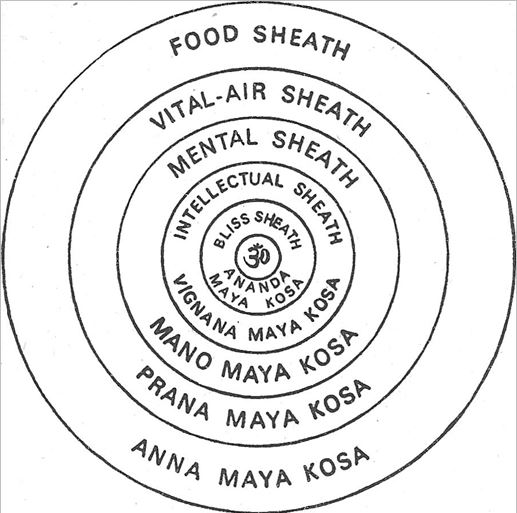

I realized recently that my misunderstanding about this metaphor came from a source that I respected highly at the time – Sri Parthasarathy’s ‘Vedanta Treatise’. (Don’t misunderstand me here – this is a good book but not everything in it can be relied upon for accuracy according to sampradAya teaching.) In this book he says: “The structure of man can be further divided into five material layers enveloping Atman. Atman is the core of your personality. It is represented in the diagram below by the mystic symbol ॐ (pronounced OM). The five concentric circles around the symbol represent the five layers of matter.” And a diagram is presented as below:

It is hardly surprising then that this sort of concept of the Atman being ‘covered over’ or ‘hidden’ is formed or taken on board by many people. And of course it must be quite erroneous. How can the Atman (which is the eternal, unlimited, infinite brahman) be covered by anything? There is nowhere that brahman is not, because everything is brahman.

The word kosha can have many meanings – a cask or vessel for holding liquids, such as a bucket or cup; a box, cupboard, drawer or trunk; a case or covering; store room, store (or even provisions); a treasury; a surgical bandage; a dictionary; a collection of poetry; a nutmeg; the inner part of certain fruit; the cocoon of a silk worm; the membrane covering an egg in the womb; the vulva, testicle, scrotum or penis (?); a ball or globe; the eye ball; an oath; a shoe or sandal; a kind of perfume; a ploughshare. (It is incredible that, when you look up a Sanskrit word in the dictionary, it often seems to have so many possible meanings that you wonder how anyone can translate the scriptures! Also the majority of words seem to have sexual connotations – and I don’t think this is my imagination!)

But the meaning that appears relevant here is given as: “a term for the three sheaths or succession of cases which make up the various frames of the body enveloping the soul.” (The reason why ‘three’ is mentioned rather than five will become clear later.) So here again we have the idea of something ‘covering’ our soul or essential nature.

Part 2 looks at the scriptural origins of the metaphor in the Taittiriya Upanishad, and the much later text of Vivekachudamani.