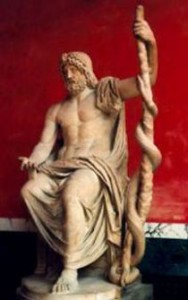

(Asclepios or Aesculapius)

Part 3 of this essay should have ended with the clarification that the statement: ‘there is no other transmigrant but the Lord’, is but a doctrine, even though a very high spiritual or metaphysical doctrine, and, as every doctrine, it is (only) mithya, that is, ultimately not real, not the “realest” real. It can be stultified.

During my long written dialogue with Peter Bonnici centering on the ‘terrestrial garden’, I had said: ” They (myth and mithya) are quite different, though there is an overlap in the way we can make use of either of them in order to bring out a deeper understanding of something that may only be implicit”.

Peter’s eloquent reply was: “There is definitely a difference between the two. Though, as you say, there is overlap. Everything, including language and stories and concepts and symbols come under the category of mithyā– their existence cannot be denied, their usefulness at the transactional level cannot be denied, but their absolute independent reality can be denied. They are expressions of sat-cit, pure existence-consciousness. And they ultimately resolve into sat-cit, a thorn to remove a thorn is also discarded at the end. There is only one thing that isn’t mithyā: Brahman, Reality, the Whole. So myths do have value and are not to be dismissed. The analogy given is of using the branch to locate the moon”.

Under this heading I will present and briefly discuss three myths from the Western World, with which I am somewhat familiar: The ancient Greek myth of ‘Asclepius’ (the god of medicine – and *resuscitation*), the Medieval play ‘Death and the Maiden’ (with the related devilish dance – ‘danse macabre’), and a modern reconstruction of the Medieval Nordic (Scandinavian and German) legend, ‘Tristan and Isolde’.

Asclepius (or Aesculapius)

Concerning this myth there is a fundamental idea underlying it and many other myths (like those of Cassandra, Sisyphus, Cassiopeia, etc. – well related, for example, in ‘La sagesse des mythes’, by Luc Ferry, 2008). Two ideas, rather, corresponding to their ‘realities’ (or pseudo-realities, depending on one’s understanding and angle of vision): hubris (or hybris), basically arrogance, pride, pretense, and its subsidiary ‘lack of measure’, both characterizing mankind and bringing about unending struggle, disharmony, and final catastrophe – individual and collective. Human history is rich in the consequences of this pair, as illustrated and reflected in many of the myths and tragedies of Greek literature. These failings are the result of ignoring (never learning) the two precepts inscribed on the frontispiece of the temple of Apollo in Delphos: ‘know thyself’, and ‘everything in measure’. The prototype of the myth having hubris as its motor is that of Prometheus, who stole the fire from the gods and the arts and technology (useful for warfare) from Athena.

The Greeks knew well these defects and the corresponding temptations, which led many in their midst to feel that they were ‘equal to the gods’, or nearly so. Where to find a humble person or, as Socrates kept asking his fellow Athenians, a wise one? At any rate, the greatest danger stemming from hubris is that it, potentially or actually, threatens to upset the cosmic or universal equilibrium, the order of things so intricately devised and developed by Zeus (or Isvara). Why so in the case of Asclepius?

Asclepius, the first and best of physicians, was not only the best of healers, but, given his extraordinary success, he also started to revive the dead, with the consequence that Hades, the god of the underworld, became concerned about the diminishing supply of potential denizens for his domain, so much so that, finally, Zeus, the supreme god and brother of Hades, had to put an end to that subverting occupation: Asclepius, without further ado, was promptly fulminated. His intention, presumably, had not been selfish or inspired by pride, but still, by so doing he was transgressing the limits of what is permissible, that is, was subverting, or threatening to subvert the cosmic order. To be noted that the serpent symbolizes re-birth, the hope of a second birth.

A sad end for that foremost of physicians, son of Apollo and Coronis, who had been forcibly taken from the maternal uterus after she and her lover were found out by the jealous god and were transfixed with an arrow sent by him while embracing in the ecstasy of love (this story has been transmitted to us by Apolodorus). A related and interesting datum is that Asclepius had been educated, on Zeus’ instructions, by the best of educators (he had been so for Achilles and Jason, of epical renown), the centaur Quiron. Nevertheless, Zeus relented somewhat after the fact and allowed for Asclepius to be for ever transformed (apotheosis) into a constellation (Serpentaria); nothing less was merited by such an exemplar physician, father of the healing arts – he is usually represented with a serpent in his hand and also a caduceus (staff) with two serpents coiled around it.

Death and the Maiden is a common motif in Renaissance art, especially in painting, and also music. It was developed from the Dance of Death. The new element was an erotic subtext. The motif was picked up again in romantic art, a prominent example being Franz Schubert‘s lied Der Tod und das Mädchen.

Dance of Death, also variously called Danse Macabre (French), Danza de la Muerte (Spanish), is an artistic genre of late-medieval allegory on the universality of death: no matter one’s station in life, the Dance of Death (dance of Shiva?) unites all. The Danse Macabre consists of the dead, or personified Death summoning representatives from all walks of life to dance along to the grave, typically a pope, emperor, king, child, and laborer. This dance had the intention of reminding people of the fragility of their lives and how vain were the glories of earthly life. Its origins are postulated from illustrated sermon texts; the earliest recorded visual scheme was a now lost mural in the Saints Innocents Cemetery in Paris dating from 1424–25.

The deathly horrors of the 14th century—such as recurring famines; the Hundred Years’ War in France; and, most of all, the Black Death—were culturally assimilated throughout Europe. The omnipresent possibility of sudden and painful death increased the religious desire for penitence, but it also evoked a hysterical desire for amusement while still possible; a last dance as cold comfort. The danse macabre combines both desires: in many ways similar to the mediaeval mystery plays, the dance-with-death allegory was originally a didactic dialogue poem to remind people of the inevitability of death and to advise them strongly to be prepared at all times for death: memento mori. (From Wikipedia).

In the first printed Totentanz textbook, approx. 1460, a short dialogue is attached to each victim, in which Death is summoning him (or, more rarely, her) to dance, and the summoned is moaning about impending death. Death addresses, for example, the emperor:

Emperor, your sword won’t help you out

Scepter and crown are worthless here

I’ve taken you by the hand

For you must come to my dance.

At the lower end of the Totentanz, Death calls, for example, the peasant to dance, who answers:

I had to work very much and very hard

The sweat was running down my skin

I’d like to escape death nonetheless

But here I won’t have any luck

The dance finishes (or sometimes starts) with a summary of the allegory’s main point:

Wer war der Thor, wer der Weise[r],

“Who was the fool, who the wise [man],

Wer der Bettler oder Kaiser?

who the beggar or the Emperor?

Ob arm, ob reich, im Tode gleich.

Whether rich or poor, [all are] equal in death.” (From Wikipedia)