Q: Advaita says that ‘sarvam khalvidam brahma – all this (including all objects, which have form) is brahman’. Therefore, how can we say that brahman is without any attributes at all (including form)? Surely brahman must be both with and without form? Isn’t this what neti, neti means (not this, not that)?

Tag Archives: mithya

Mithya, Mythology, and Metaphysics – an exchange

(Under part 4 of my ‘Review of article on Shankara’ 9 ‘thoughts’ or

comments were made, the last one on May 8th, 2013. Following that,

Peter and I continued our dialogue, which took us in different

directions, resulting in a 12 page thread. We both thought that our discussion might merit publication in AV. Quite sadly, Peter passed away one week after he wrote his last reply within our exchange. This is the first part, to be followed sequentially).

Martin (M) – How interesting that myths (different from ‘mithya’) give rise to different interpretations, perhaps mostly due to one’s cultural background and held views on life, etc. When you say ‘literal’, in this context, I understand something like an interesting story, mostly for children; but if myths say something about man’s life, his struggles, aspirations, etc., how can they be just nice, imaginative stories? (‘literal’ x2 is for those who believe – in the recounting of The Garden of Paradise – that that is how it actually happened; I don’t count you among them, of course).

About your points (Peter’s (P):

- Right, not unity, but union (Creator/creature, lover/beloved, etc.); therefore bhakti, with its bond of love and surrender on the part of the creature – which can lead to a state of unity (advaita) once Knowlege or realization has dawn. No?

- a) “with us” is not plural; it is first person singular when the subject is God, a king, or someone in authority speaking for the law or from a chair of authority, which is impersonal. If you have the KJ version of the Bible, it reads: “man is become as one of us, to know good and evil” Gen., 3, 22.

b) P: “Before Adam was ‘one with’ God, (i.e. before he knew right from wrong), what was he?” My (M) answer: ‘one of us’ sounds rather sarcastic, No? Yes, man knew duality by his ‘individualistic’ act, but was not like God; this cannot be the meaning of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). With the New Testament, things are no longer oppressive, based on fear and ‘the law’: Jesus brings liberation through knowledge, love, and compassion, and man is seen as theomorphic (capable of assuming his divinity in Oneness). cf. St. John’s Gospel and the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas.

- a) M: The serpent “presaging Jesus”? At one time Jesus said: “you must be wise as serpents”, meaning to discriminate between acts (and people), but, other than that, the serpent is ‘the Tempter’ and the representation of evil (egotism?), and henceforth there will be enmity between it and mankind (“it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel” (Gen., 3,15).

b) P: “what’s wrong with having the knowledge of right and wrong?”.

M: ‘Seeing’ duality everywhere*, precisely – the pairs of opposites – and thus becoming judgmental and stuck in that limited, constricted vision, the consequence being the loss of Paradise in union with God. “You will be like gods” was the promise of the serpent. Duality (plurality) pertains to the dimension of God or Ishvara (‘I’ and ‘other’, heavens, hells, etc.). Right and wrong belong to thinking (vritti/s), as you well know, and it can be a problem unless you just observe it as such (i.e., an object for Consciousness). Did the couple know that they were immortal? I don’t know, and probably they did not know either. Continue reading

Q. 350 – Heaven and Hell

Q: In Advaita, it is said that the heaven and the hell are mithya. They are just ideas for bhakti-natured people. But Advaita says this world is mithya too. So even though heaven and the hell are mithya, we are still gonna go there just as this world is mithya but it is still real enough for us? I mean the idea of heaven and hell is mithya but it is still as real as this world. So they indeed exist just as this world. Is that the correct interpretation?

A (Ramesam): Firstly the simple and straightforward answer: Yes, you are right, heaven and hell are mithya and are ideas for bhakti-natured people, in the sense that they are experienced by the people who believe in them but these loka-s (worlds) lack a substantive reality by themselves. However, we have to note that they are the second degree imaginations – imaginations of the already imaginary worldly people! By this logic, perhaps they will be strictly comparable to dreams in their order of reality. (The word mithya includes both the empirical (vyavaharika) reality and the dream world (prAtibhAsika) reality). Continue reading

Origin and Meaning of the word mithyA

Seekers often ask questions about the meaning of the word mithyA. It is, after all, one of the most important concepts in Advaita. Someone has just asked about the usage of the word itself: Did Shankara use it? Does it occur in the Upanishads? I had to do a bit of research on this one and thought others might be interested in what I discovered.

The dictionary definition of the word gives: 1) contrarily, incorrectly, wrongly, improperly; 2) falsely, deceitfully, untruly; 3) not in reality, only apparently; 4) to no purpose, fruitlessly, in vain. According to John Grimes, it derives from the verb-root mith, meaning ‘to dispute angrily, altercate’.

It seems that it only occurs in one Upanishad – the muktikopaniShad. This is the Upanishad which tells you which Upanishads you need to study in order to obtain mokSha or mukti. It says that you can, in theory, get away with studying only one – the Mandukya, with its bare 12 sutras. If this alone does not enlighten you, then you need to study the 10 major Upanishads (Isha, Kena, Katha, Prashna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya and Brihadaranyaka). If you still haven’t got it, there are a further 22 making up the main ones. Failing that, you are doomed to have to study the 108 commonly recognized ones. (After that, you start again!) Continue reading

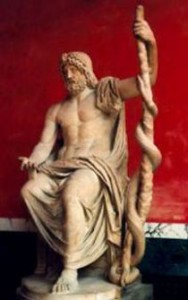

What is Death – part 4 (Mythology).

(Asclepios or Aesculapius)

Part 3 of this essay should have ended with the clarification that the statement: ‘there is no other transmigrant but the Lord’, is but a doctrine, even though a very high spiritual or metaphysical doctrine, and, as every doctrine, it is (only) mithya, that is, ultimately not real, not the “realest” real. It can be stultified.

During my long written dialogue with Peter Bonnici centering on the ‘terrestrial garden’, I had said: ” They (myth and mithya) are quite different, though there is an overlap in the way we can make use of either of them in order to bring out a deeper understanding of something that may only be implicit”.

Peter’s eloquent reply was: “There is definitely a difference between the two. Though, as you say, there is overlap. Everything, including language and stories and concepts and symbols come under the category of mithyā– their existence cannot be denied, their usefulness at the transactional level cannot be denied, but their absolute independent reality can be denied. They are expressions of sat-cit, pure existence-consciousness. And they ultimately resolve into sat-cit, a thorn to remove a thorn is also discarded at the end. There is only one thing that isn’t mithyā: Brahman, Reality, the Whole. So myths do have value and are not to be dismissed. The analogy given is of using the branch to locate the moon”. Continue reading

Musings on Life and Death

![]() Hearing of our friend Peter’s death, Dhanya commented Death is a strange phenomenon in our world. One minute the person is alive and available, and the next minute totally gone, thereby summing up in simple words how it feels to experience the death of another person.

Hearing of our friend Peter’s death, Dhanya commented Death is a strange phenomenon in our world. One minute the person is alive and available, and the next minute totally gone, thereby summing up in simple words how it feels to experience the death of another person.

Reflecting on her statement, I came to look at death from the perspective of the dying one – noticing that life turns into as strange a phenomenon as death.

Perceiving with these mithyA-senses and this mithyA-mind a mithyA-body-mind entity called Sitara that is part of a mithyA-universe, whirling and twirling around in orderly beauty. All of this is obviously ‘here’ and yet also dreamlike, for neither Sitara nor the universe has always been here, nor will they eternally remain here in this form. All phenomena are in a constant flux, forever appearing and disappearing to something that is itself neither alive nor dead nor even different from the appearances and disappearances themselves.

Life is such a colorful, diverse, multidimensional phenomenon and, to almost everyone, it seems to be absolutely real. Yet it does not serve any purpose except for one peculiar one: to realize that this full explosion of creativity is no more real than the moon’s shining.

What a strange phenomenon is life – and how blessed is everyone who knows him/herself as life, death and beyond.

Photo credits: luise@pixelio.de

Q. 346 – brahman, Ishvara and mAyA

Q: I am not clear about the relationship between Brahman, Maya and Ishwara. Maya is said to be inherent in Brahman. Like Brahman, it is ever existent. Ishwara is said to be a product of Brahman and Maya. However, while the universe is governed by Maya, Maya does not govern Ishwara. Ishwara governs Maya although he is a product of Maya. This is confusing.

Secondly, did Shankara deviate from the teachings of Upanishads? The invocatory verse in Ishopanishad, Purnam idam, Purnam adaha, Puranat, Purnam utpadyate seems to indicate that this world is born out of that Brahaman. Shankara does not seem to agree with this view. According to him, the imperfect limited world cannot emerge from unlimited, perfect Brahman and the world is only an illusion created by Maya. What is the correct position? Continue reading

upadesha sAhasrI part 12

Part 12 of the serialization of the presentation (compiled by R. B. Athreya from the lectures given by Swami Paramarthananda) of upadesha sAhasrI. This is the prakaraNa grantha which is agreed by most experts to have been written by Shankara himself and is an elaborate unfoldment of the essence of Advaita.

Subscribers to Advaita Vision are also offered special rates on the journal and on books published by Tattvaloka. See the full introduction

Review of article on Shankara – Part 6, and final

Maya

Maya

A tarka (reasoning, argumentation) is required for the analysis of anubhava, as both SSS and RB agree – consistent with Shankara’s position. That is, language and thought, needless to say, have a role to play, chiefly for exposition and analysis.

However, after two long, dense paragraphs RB contends: “If the tarka required to examine anubhava is itself completely dependent on ´sruti, then by no means is anubhava the ‘kingpin’ of pram¯an.as.”

Prior to this, SSS was quoted as maintaining that “for this unique tarka all universal anubhavas or experiences (intuitive experiences) themselves are the support.” The author states that this affirmation involves circular argumentation, and that to say that Shankara interprets the Vedas as being consistent with anubhava is wrong, the truth being the opposite: anubhava is consistent with the Vedas: “it should be clear that according to Sure´svar¯ac¯arya, the direct realization is directly from just ´sruti itself, thus satisfying the criteria for it to be a pram¯an.a…. The direct realization of the self is from ´sruti alone.” Continue reading

Logical enquiry into ‘Who I am’ (4/4)

We started this enquiry into identity by employing a simple piece of logic: you cannot be what you observe. From this point of view, the things we normally take ourselves to be, starting with the body, were systematically discounted because they turn out to be objects of perception, as covered in the first three parts of this series. Despite this reasoning, the tendency to believe our identity with the amalgam of body, senses and mind tends to remains very powerful: we continue to believe that we are these individuals bound by skin, with an experiential history and an instinctive, habitual mindset through which ‘I’ filter the world.

We started this enquiry into identity by employing a simple piece of logic: you cannot be what you observe. From this point of view, the things we normally take ourselves to be, starting with the body, were systematically discounted because they turn out to be objects of perception, as covered in the first three parts of this series. Despite this reasoning, the tendency to believe our identity with the amalgam of body, senses and mind tends to remains very powerful: we continue to believe that we are these individuals bound by skin, with an experiential history and an instinctive, habitual mindset through which ‘I’ filter the world.

Identity with the body is evidenced by the vast cosmetic surgery industry today. People feel better with fewer wrinkles, larger breasts, drug-induced libido, less fat, etc. That’s the extreme end, but coming closer to the average person, we think of ourselves as too tall, too short, too hot or cold. If the body is in pain, we say: I am in pain. We really do mean ‘I’ when we say: I am hot, cold, ugly, beautiful, too short, too fat, too old. By employing the incontrovertible logic of ‘I cannot be what I can observe’, it does not take long for us to realise that the body is an object of perception: ‘I’ can experience my body using my five senses. We then ask: Who is observing the body? Continue reading